Imagine you are hearing impaired. You normally rely on close captioning when watching movies or videos. Quite suddenly, as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, you and your entire department are working from home. You open your laptop and click on the link for your first weekly video conference meeting. You see your coworkers pop up in their little windows in gallery view. You hear nothing, and there are no closed captions. Now imagine that you are viewing a news report on television. Normally, you could read their lips, but due to the masks they are now wearing as a requirement, you cannot see their mouths.

The Covid-19 pandemic has sent both businesses and individuals scrambling to provide the necessities that allow people to work and shop remotely, and at the same time it has left people with disabilities at a disadvantage yet again, everyone else now has a window into what they face every day. Will I be able to work from home? How will I get groceries? Is there enough space on the sidewalk or in the store aisles for me? With social distancing in place, these problems that people with disabilities have always had to address are finally being felt by the rest of society.

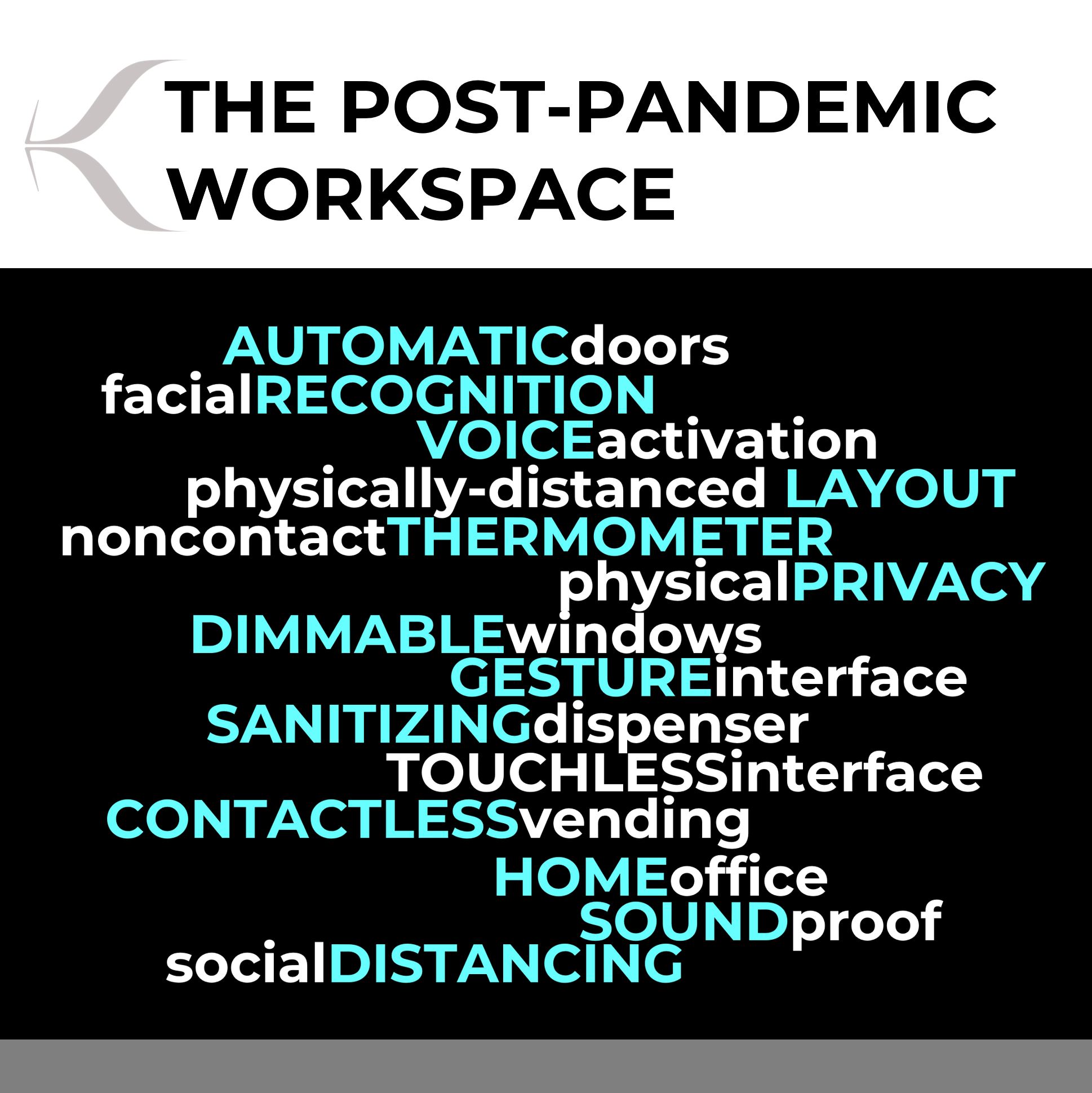

Automatic doors that reduce the transference of germs are also of great assistance to people who use wheelchairs, walkers and service dogs as are the wider walkways that promote social distancing. Technology, and a willing employer, that allows people to work and participate in meetings from afar can also be vital to the productivity of those with mobility issues or chronic illness.

If played right, this new, greater focus on accessibility can lead to across-the-board changes to product and interface design beyond simply what makes sense from an infectious disease standpoint. If we listen to the voices of people with disabilities during the design phase, we can create a world in which spaces and interfaces work better not just for disabled people, but for everyone. And with public and workspaces friendly to all, we improved everyone’s experience of common space.

Since the advent of Covid-19, we have all begun to rely more on technology, but is that tech accessible to everyone? People who are blind or visually impaired experience more extensive barriers to using the internet than any other group. The contrast, or lack thereof, between background color and text can be prohibitive for people with low site. And, even with a screen reader, scanning long pages for pertinent information can be problematic, especially if headings and subheadings are not coded appropriately to be recognized by the digital reader as such.

The voiceover, the go-to feature for services geared toward people who are visually impaired, could stand considerable improvement in terms of modulation, speed, and clarity. A feature that reads through grocery store information as a person shops, for example, would do well to focus on only what is pertinent, sorting through the clutter so as not to be overwhelming. Online, while many images have alternate text which can be read by an automatic screen reader, the literal description of a picture is not often the most helpful; text explaining the image’s intention or what information it links to would be more useful. There are also hardware-oriented aspects of web access to consider. Can users of limited physical ability access the full functionality of a website using only a keyboard or only a mouse?

Going forward, these are issues we can prioritize at the beginning of the design phase of a building, a public park, an internet shopping interface, or work-from-home software. Perhaps the push Covid-19 has given us toward more robust systems will spur us to design more universally, for the optimal use of everyone who will access them, no matter their ability.